Pieces of a City in Flux

Megan Hullander

Chris Friday, “Narcissist,” 2023, installed outside MOCA North Miami. Courtesy of MOCA North Miami.

It’s strange that Miami’s broader reputation remains built upon fake tans, early-bird specials, and bottle service—at least enough so to curtail longstanding intrigue from the urban elite. In reality, those qualifiers are small pieces of Miami’s greater, fragmented identity. It was dubbed “The Magic City” in the late 1890s as a marketing ploy intended to lure settlers to its eternal summer. It worked: By the 1920s, the city experienced an unprecedented boom in real estate and tourism.

That growth maintained as Miami became the recipient of various exoduses, taking periodic populations of immigrants and tax-evading retirees. More recently, it has labeled itself a crypto capital, successfully encouraging a substantial migration of Silicon Valley runaways its way. This year’s acquisition of Lionel Messi for a once hugely failing MLS team positions the city as an early site for transforming an insubstantial American “soccer” stadium into an internationally respected “football” league.

Miami is a city in flux, defined by its ability to absorb and propagate cultures and communities in fast succession. There are physical pieces of it, though, that persist—in the art that occupies its permanent collections (which count John Baldessari’s Choosing (A Game for Two Players): Chocolates, Keith Haring’s USA-19-82, and Iggy Pop’s melted bronzed abs (and the rest of the musician) among them) and, more enduringly, in its disparate architecture. Miami is made of a multiplicity of identities: the picture-perfect postcard of sandy beaches and cerulean seas, the punk hub, the Cuban oasis, the emerging art scenes. The city is fast-changing, and so its structures exist among the few lasting relics of its many identities.

Relic (1) is an explicit instance of historical preservation. In South Beach, sandwiched between crumbling art deco and vape shops, The Wolfsonian stands with foreboding allure: white and windowless, encrusted with carved sandstone frieze. Originally constructed during that population boom in the ’20s, the building—like many structures of its time—was designed to resemble the architecture of the Mediterranean coast to further propagate its coastal allure. Initially serving as a storage facility, the building took in Mitchell Wolfson Jr.’s expansive collection of rare objects and books in the late-’80s. His high-end cache quickly swelled to fill 90 percent of the building’s space, prompting his purchase of it and its subsequent development into the museum. A new exhibition, Silhouettes: Image and Word in the Harlem Renaissance, starts around the same period in which the building was first constructed. Looking north to the New York neighborhood, the show charts the artists in the ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s who painted a less publicly-familiar picture of Black life, marked by a collaborative spirit.

Also migrating to Miami is Public Enemy, which turns its eye to the societal evils to which Black communities have been subjected. Surveying more than three decades of multimedia examinations of racism in American culture, Gary Simmons’s work is even more striking against the natural ease of Relic (2). Pérez Art Museum Miami was designed by Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron in Downtown Miami in response to its environmental circumstance: situated on the waterfront, the building is elevated on stilts to protect it from storm run-off; its exterior walls are made of glass, offering views of the surrounding nature; a canopy that hangs over its whole coupled with tropical plants produce a microclimate within it.

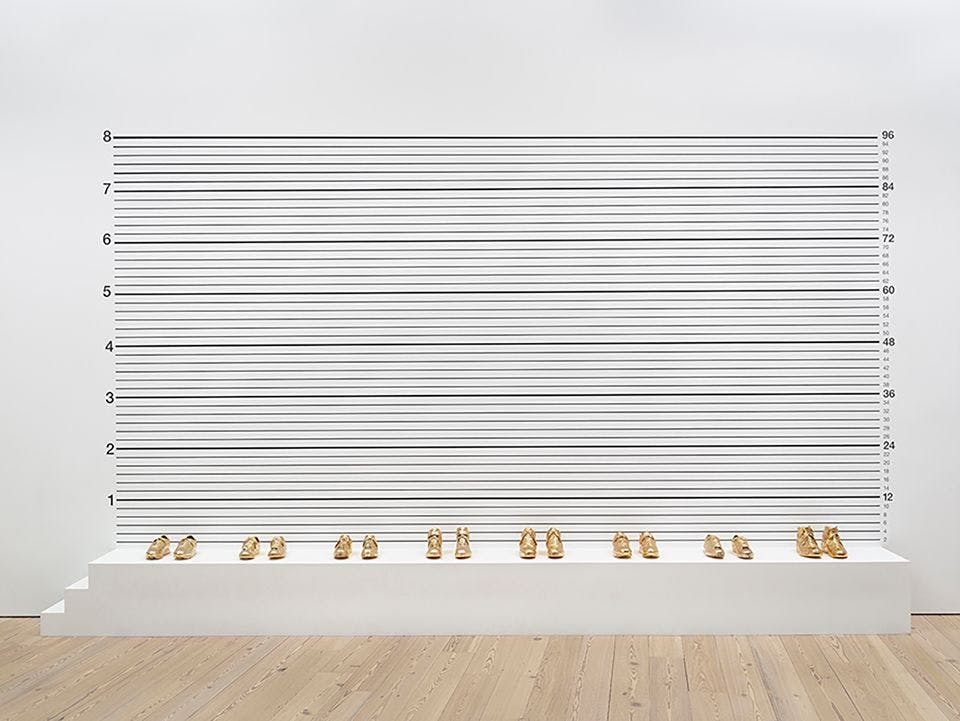

PAMM lives in Miami’s Biscayne Bay, a picturesque lagoon with shallow waters drawn in full-bodied Crayola colors, palm trees that stretch over warm sands, and dense mangrove forests. The themes of Public Enemy are made especially confrontational against their new tranquil surroundings. Eight pairs of gold-plated trainers glint in the sun, with an enormous police height chart serving as its background. The remains of a 1964 World’s Fair pavilion painted in pigment and oil stand in the foreground of a vibrant blue canvas, its color becoming almost sickly saccharine against the warm Miami water just steps away.

Relic (3) is fueled by change. The Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami is founded on the ever-evolving now and new. It’s a piece of imagination in North Miami, equipped with walkways to government structures like the local police department. Jamea Richmond-Edwards’s forthcoming Ancient Future at MOCA North Miami indulges in the fantasies of the past, reimagining Afro-futurism and Black mythologies in paintings, films, and installations. Richmond-Edwards overlays the past with the present and the future in references and material: Egyptology blends with biblical imagery, historical figures are displayed beside self-portraits, natural disasters converge with the cosmos.

The design of MOCA North Miami itself employs more empirical imaginations for the future. Founded in 1981, the Center for Contemporary Art ballooned in 1996, transforming its modest single gallery into a 23,000-square-foot facility and adopting a new name the following year. MOCA’s strange and striking layout is designed to encourage the flow of art in and outside the building. For MOCA North Miami, modernity is rooted in accessibility, and so, it plans to further open itself up in a forthcoming renovation of its outdoor plaza that will introduce new light fixtures, space designed for group activities, and trees lining pathways to City Hall and the nearby police department.

Relic (4), the Institute of Contemporary Art opened in Miami’s Design District—which hosts more than 100 galleries, showrooms, architecture firms, antique dealers, and luxury fashion stores—in 2017. It's constructed to replicate a magic box, its exterior wears shiny, geometric shapes. Its back is lined with large windows looking onto a sculpture garden below. Fitting for the internet era in which it was designed, the aesthetic of its facade is a principal piece of its reputation, made to resemble a large-scale, textured magnet, drawing visitors its way with its reflective sheen. It’s appropriate, then, that it should host the work of Charles Gaines, whose work is considered pioneering to conceptual art, especially through his employ of technical mechanisms. Charles Gaines: 1992-2023 spotlights the second half of the artist’s career, seeing him engage with materials of historical weight—including the Black Panthers’ manifesto and texts from Franz Kafka—for multimedia pieces.

Relic (5) outgrew its first home. The Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum was born in Florida International University’s Primera Casa building in 1978, but over the following decades it expanded, requiring a building of its own. Its new home, which opened in 2008, is L-shaped, constructed around a lake and ficus tree on the University’s campus in Miami. Its structured angles and curves made from pink-gray granite appear more minimalistic when occupied by Embellish Me, a selection of works from the collection of Norma Canelas Roth and William Roth. The exhibition primarily features pieces from the Pattern and Decoration movement, filling the space with meticulous embroidery, delicate mosaics, and complex fiberworks.

Relic (6) bears patterns in its symmetry. The Bass Museum was one of the first Art Deco structures to grace the city, designed to mirror the gardens of Collins Park. The style, which eventually became definitive in Miami, was intended to prompt a sense of pride amid the Great Depression. In an exhibition that will overlap and extend beyond Basel, The Bass will stage Social Assembly: Welcome to the Museum, premiering alongside the reveal of the gallery’s original windows. The works of Social Assembly are supposed to challenge how audiences interact with and learn from art, and the newly unveiled windows will offer a means to do just that, introducing transparency between the museum’s interior and exterior. Unique to The Bass’s makeup is its oolitic limestone cladding. Coupled with its carved ornament, it resembles the Mesoamerican architecture of the Yucatán—a tangible emblem of the city’s desire to become the primary link between North and South America.

The self-conception of Miami as a city of the future is undoubtedly tenable. Flashy and trashy, upscale and accessible, its humidity is matched only in its density of mores. Miami’s many pasts will always permeate into its present, made of ever-proliferating layers of culture.