New Ways of Seeing

Franklin Sirmans, Pete Scantland

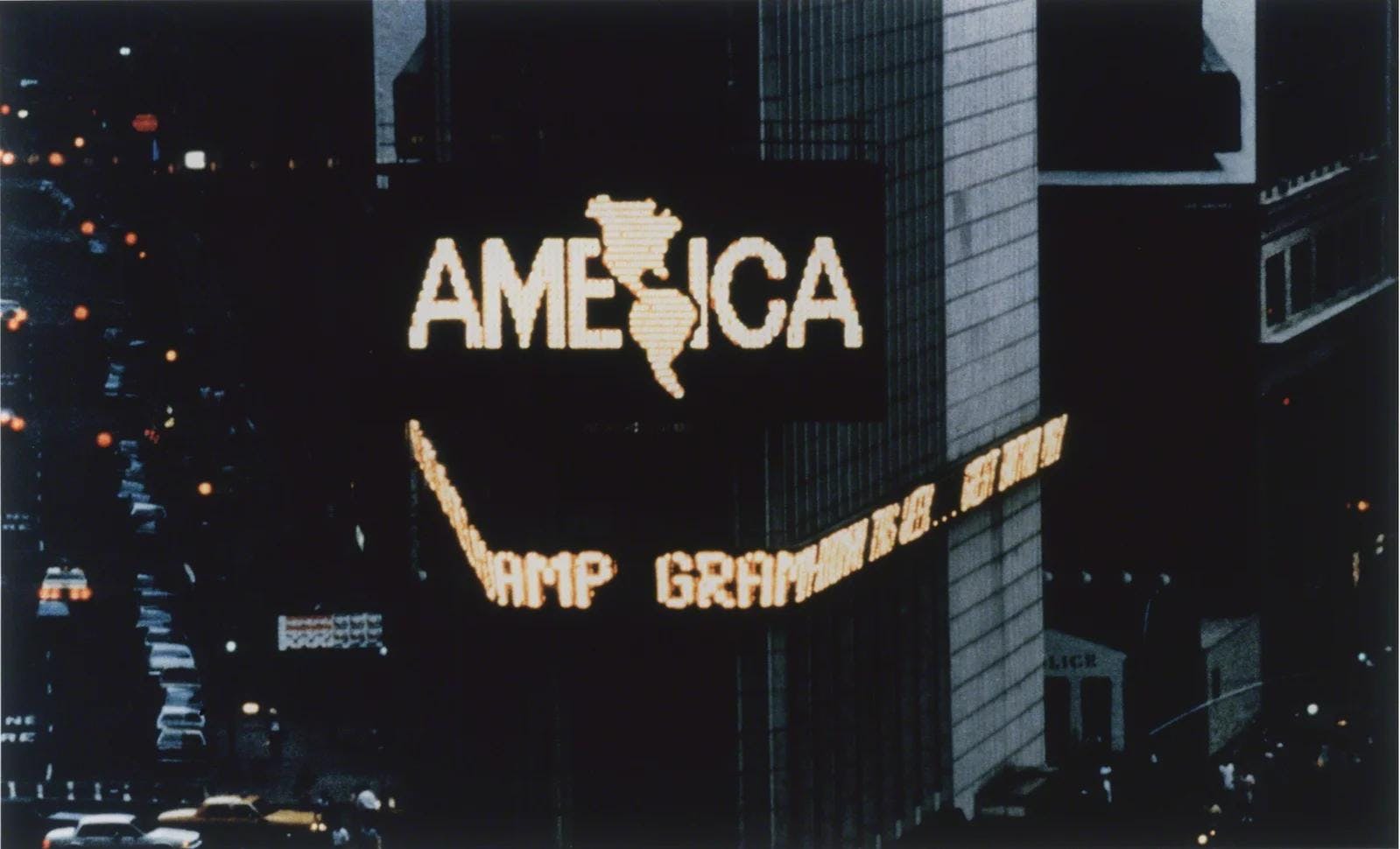

Alfredo Jaar., “A logo for America,” (1987-1995). Courtesy: PAMM.

There’s no shortage of things to look at in Miami, especially during Art Week. Now, a partnership between the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) and Orange Barrel Media bringing monumental digital signage to the Museum’s grounds is more than the latest addition to Miami’s topography of glamor and capital; it’s a case study in alternative revenue streams for museums across the country. It’s also the latest move to blur the line between art and mass media. To discuss this partnership—and the relationship between art and advertising—we spoke with Pérez Art Museum Miami Director Franklin Sirmans and Orange Barrel Media CEO Pete Scantland.

Discovery: How did you guys come to work together?

Pete Scantland: Our company, Orange Barrel Media (OBM), has been working with arts institutions for a long time, primarily as a content partner. In many cases, we’d commission an artist to make work for our digital signs, or we would help them to promote an exhibition that was happening inside the museum. In the back of my head, I was always thinking, could we do this at an art museum and combine some of the work we're doing as content partners with a business partnership?

Because in many cases, museums are blessed with a prominent building that, if it were anything other than a museum, would solve a lot of their financial problems. PAMM, if it weren’t serving the public, would be one of the most valuable pieces of land in Miami. It could be condos. This is a way for them to not only open up a window into what’s happening inside of the museum to the hundreds of thousands of people who drive by every day but also to create a revenue stream that’s independent of box office and all of the more traditional earned revenue channels that museums have worked so hard to develop over the last 20 years.

Franklin Sirmans: Making use of our architecture and our location wasn’t brand new to us. We are directly across the water from the Children’s Museum here in Miami, which has a pretty significant digital sign on the side of its building. We’re in Downtown. We are right next to the highway that goes between Miami and Miami Beach. We are right across from the arena where the Miami Heat play. So we’re part of this constellation of potential opportunities around… I hesitate to use the word “advertising” because it’s more than that. It’s like talking about Times Square. When you talk about Times Square, my reference point to Times Square always had art in it. I grew up in New York in the ’70s and ’80s, and the billboard was used as an art space; not all the time, but periodically. We have a work in our collection by Alfredo Jaar that comes directly from that. So there’s that kind of opportunity that’s in the back of our mind when we think about signage and its presence within the growing orbit of Downtown Miami.

The idea that it could be something special meant that it had to be with a special partner. We had been approached by other folks more traditionally, and let’s say there wasn't so much of an appetite for engaging in that way, because what is the point? Where does the art come from? What is the difference? What sets us apart? How is this contributing and not just about us trying to make a little bit of money? That's not our thing. We’re a nonprofit. And so from the moment we started talking and learning more about Pete's collection individually, personally, and his relationship with artists, in addition to, of course, our curatorial bridge, something felt right.

OBM has new ways of seeing. They have to because that is the focal point of their presentational spaces. And so I think we’re learning from each other. We’ve got a curatorial team here, they’ve also got a curatorial team, and we're exchanging ideas and trying to figure out how to move the needle forward.

Discovery: That piece you mentioned, “A Logo for America” by Alfredo Jaar, was in the first collection show when the museum opened. You walked past the ticket desk and that was the first thing you saw. Pete, let's talk about your story here. How does collecting and working in advertising come together?

Pete Scantland: We’ve always tried to use our medium to benefit art, which has been my passion since I was a little kid. Artists and institutions are interested in working with us, frankly, for the same reason that brands are: because they want to reach a lot of people. They want to do it in a channel that is impactful and that people notice. As Franklin mentioned, there’s a long tradition of artists not only learning the devices of how to communicate effectively but also using the channels that commercial actors use. And many artists started in communications. You can think of everyone from Andy Warhol to James Rosenquist, to Barbara Kruger, to Ed Ruscha, and many of the young artists today. Right now I’m looking at a painting by Jaime Muñoz, who started as a sign painter.

In art school and advertising school, you learn many of the same formal approaches and many of the same devices. Artists today know how to use mass media, for their work to have more of an impact. Hank Willis Thomas, an artist with whom we work a lot, is a brilliant artist, but part of why he's making such a big impact in the world is because he is also leveraging the tools and techniques of commercial marketers, and doing so in an effective way that has allowed him to share his work and the work of other artists with a much bigger audience. We're excited to be a part of that.

Discovery: Franklin, for the readers who can’t have the pleasure of being on this Zoom with you guys, I’m looking behind you at a Kehinde Wiley painting that is part of the marketing campaign LACMA created for Fútbol: The Beautiful Game, the show that you put together back in 2014. From your early work with Basquiat, up to the show, which will be open at PAMM, Gary Simmons: Public Enemy, you often engage artists who are exploring popular culture or exploring ways of communicating with larger audiences.

Franklin Sirmans: It’s huge. The thing that came to my mind while listening to Pete is the relationship between that outdoor public presentational space and its relationship to graffiti and to the history of writing that you touch on a little bit, in mentioning Basquiat in particular. Artists have strived to share their work with the world for a long time. We throw around the term “art world,” and we know what we’re talking about when we say it, even though we know that there are different art worlds. But so much of what I find interesting in artists today is this thing that we’ve been striving for, which is that [art is] a part of everybody’s life. It’s not a rarefied space, these types of presentation spaces are out there in the world. Like all of the artists that we’ve mentioned, it allows people to have a better understanding of what artmaking is and why it’s important in our lives, as opposed to just something for a small segment of society.

That part has always been central for me since the first large exhibition I ever worked on, One Planet Under a Groove: Contemporary Art and Hip Hop. It was trying to tap into this idea that there is something way bigger that informs a contemporary artistic practice, just like those artists Pete mentioned. Design, fashion, and comics—those were the languages of a much wider public, and thus Warhol, Ruscha, and Rosenquist would tap into those spaces to highlight the fact that there is something for everyone inside of artmaking. If you’re a contemporary artist working today— Marco Brambilla, for instance— you're working in this space; a space that is still evolving and dynamic and yet is capable of speaking to wide swaths of humanity.

You mentioned Kehinde. He's been able to do that not only through the paintings, which we all know and love, but I have so many friends who know Kehinde because of the bags, or he’s got his art on jackets. It’s a different kind of enterprise which allows for it to speak to so many different people. But it all begins with the painting. It all begins with the work of art.

Discovery: This conversation particularly is apt to come out on the eve of Miami Art Week. What do you all think about the backdrop for this partnership and your respective missions with OBM and PAMM?

Franklin Sirmans: We get to have this one week a year that celebrates art. It has changed how people think about art in the broadest context you could imagine. It’s not a foreign word. It’s cool to do. It’s something social, it’s something dynamic, it’s something entertaining, it’s something fun.

Pete Scantland: One of the great things about Art Week is that it means different things to so many people. For some people, it’s about showing up on Wednesday at 10:00 AM for the first look at the fair. But for a lot of people, it’s going to the museums, it’s going to events. You go to Franklin’s party on Thursday night where there are a couple thousand people there who are just out celebrating each other, celebrating art, celebrating Miami—this amazing-amazing city that is attracting people from all over the world to come and celebrate art for a week every year. So it’s terrific. It’s a terrific way to showcase art.

Franklin Sirmans: We’re talking about a new space to present art. We’re talking about that digital component that everybody’s exploring. I think a little idea of the potential around structure will be in some people’s minds because they would’ve seen the Sphere [in Las Vegas]. But the thing that struck us immediately, and I say us because it was all of us, was that we were making a sculpture. We’re making a structural thing that is an innovative work of art in itself. I had one person on my committee who went to L.A. to see the structure of what OBM made on Sunset Boulevard. That was the thing where it was like, oh, now I get it. It’s not just a digital thing. It’s a thing. As an artistic institution, we better be going in that direction.

Pete Scantland: One of the things that we've been focused on at our company is how we could redefine the formal qualities of the structure itself to be something beyond the typical sign-on-a-stick typology that has been standardized within our industry. [For PAMM,] that requires us to develop new content that is specific for this location and that makes everyone go out and think about this more deeply, of what works in this context with this audience, with this kind of mode of experiencing it in terms of how people are going to interact with it and to develop something that's a unique solution for this site and all of our sites. That is one of the things that we’re always focused on—what new form can we come up with that works for this location? We’re excited about what we’ve developed in partnership with PAMM.

Discovery: What will be on the screen during Art Week?

Pete Scantland: There will be two different screens. What’s up right now is on PAMM’s eastern side, where all the gatherings are. That screen is up right now, and a hundred percent of the time it will serve PAMM. Artist commissions, and if there's an event, it could be a backdrop for the performers, that kind of thing.

Franklin Sirmans: It will be another space for artists to play around and experiment. In this iteration, we will have some content by the performing artist George Clinton on Thursday night.

Pete Scantland: That's going to be amazing. The second component, which we plan to launch in February, is at the northwest tip of the property, adjacent to the building and visible to the Causeway and to 395. That will be a combination of PAMM-related content and commercial content. That’s what powers the business model that we've talked about. PAMM will be the largest single user of it, but there will be other brands that will use it as well. The fees those brands pay to use it enable the investment in the infrastructure itself and the financial benefit that supports PAMM’s mission.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.